The military has a mental health problem. The rate of suicide among service members in the United States has been climbing since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, fueled by an inherently high-stress work environment and a persistent organizational culture that views asking for help as a weakness. Roughly three-quarters of service members who take their own lives never seek mental health services, according to Craig Bryan, associate director of the National Center for Veterans Studies at the University of Utah. But it isn’t just soldiers going off to war who account for this climb in suicide rates. The majority of service members who attempt or complete suicide have never deployed, according to the Department of Defense.

Rather, experts believe that a dangerous feedback loop of daily stressors—including financial, legal, or relationship troubles that even those of us with less-harrowing jobs face—erode resiliency, leaving soldiers more susceptible to potentially traumatic events. This problem isn’t limited to the United States. Researchers and military leadership around the globe have been scrambling to develop programs to maintain or rebuild that resiliency and lower the risk for service members. The techniques developed for and by service members can trickle down to civilians—as happens with many military technologies (caffeine-laced gum, anyone?)—and help us all deal with whatever stress life brings our way.

Virtual Meditation Retreat

At Fort Sam Houston in Texas, Valerie Rice, a researcher at the Army Research Laboratory’s Human Research and Engineering Directorate, is combining an age-old stress buster—guided mindfulness meditation—with a virtual world to help soldiers cope with stress wherever they are.

Research on mindfulness meditation in civilians has already shown that the practice is good for our brains and bodies, but given the fact that soldiers are often hesitant to use mental health services, Rice wondered if soldiers would see the same benefits from an online program. “You still have soldiers and veterans who won’t come to an in-person training, even if it’s not in a health care setting,” Rice says. She thought a virtual setting might give participants a protective shield of anonymity.

In Rice’s ongoing, as-yet-unpublished study, participants create avatars and enter a virtual world where they meet up with other participants and a trainer in a virtual gazebo to learn mindfulness-based stress-reduction techniques inspired by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Preliminary results suggest that this training eases stress, anxiety, and pain and appears to increase participants’ attention span, “which is really important to active-duty soldiers,” Rice says. And the subjects’ trust levels in the virtual trainer and group members were nearly as high as in-person trust levels, according to Rice.

When we imagine ourselves doing something, it activates the same neural networks that fire when doing the same thing in reality.

This is all in line with research of other virtual worlds, like Second Life, showing that people are more likely to do things in the real world that they watch their avatars do online—like eating healthy and exercising, for example. One of the participants in Rice’s study even tried out a new hair color on her avatar before adopting it in real life. One reason virtual training may work so well is that when we imagine ourselves doing something, it activates the same neural networks that fire when doing the same thing in reality. In other words, visualization, whether virtual or just in your head, can have tangible benefits.

Rice, who spent 25 years on active duty, recognizes that introspection will not come easily to everyone, and she is still battling the sentiment among many soldiers that meditation is a “soft” option. “You know, samurai warriors are supposed to be some of the best warriors that ever lived,” she says. “They all meditated.” Many of the reasons that make the training ideal for service members—the option for anonymity, the ability to access guided meditation groups from anywhere with a computer—would appeal to civilians as well.

Rescue Center for Traumatized Animals and Vets

At the Lockwood Animal Rescue Center, a 20-acre facility in Frazier Park, California, a motley pack of dogs trails the center’s keepers, Lorin Lindner, a clinical psychologist, and her husband, Matthew Simmons. Wolves and wolf dogs keep a watchful eye on the couple from behind the chain-link fences that make up the facility’s 22 enclosures, which house dozens of rescued dogs, foxes, coyotes, wolves, primurine horses, even a parrot. At Lockwood, veterans participate in a work therapy program in which the traumatized animals and traumatized veterans can heal together.

The origin of the Warriors and Wolves program can be traced back to the late 1990s, when Lindner was the clinical director of the New Directions for Homeless Veterans program in Los Angeles. On weekends, she would take vanloads of the veterans she was treating to Ojai, where she was building a sanctuary for rescued parrots. Lindner felt the vets weren’t that engaged in traditional therapy sessions during the week. “These veterans are sitting there with their arms crossed,” she says. “So I bring them up to the sanctuary, and I see them interacting with the birds in a remarkably different manner.”

Decades of studies show that interaction with pets and animals can reduce one’s blood pressure, increase levels of oxytocin, and may even help us live longer.

At Lockwood, the veterans are full-time employees, responsible for feeding the rescued wolves and wolf dogs, cleaning out their enclosures, and socializing the animals, all while forming deep bonds with the typically reclusive creatures. Decades of studies show that interaction with pets and animals can reduce one’s blood pressure, increase levels of oxytocin (a neurotransmitter that, among many other things, plays a large role in our mood), and may even help us live longer.

“When [the animals] choose you, it’s a pretty special relationship,” Lindner says. “A lot of these veterans haven’t felt special in a while.” That relationship and responsibility, in addition to the employment, help traumatized veterans stay sober, obtain housing, reunite with family, and feel a part of a community—all crucial pillars of recovery.

Future Chill Pill

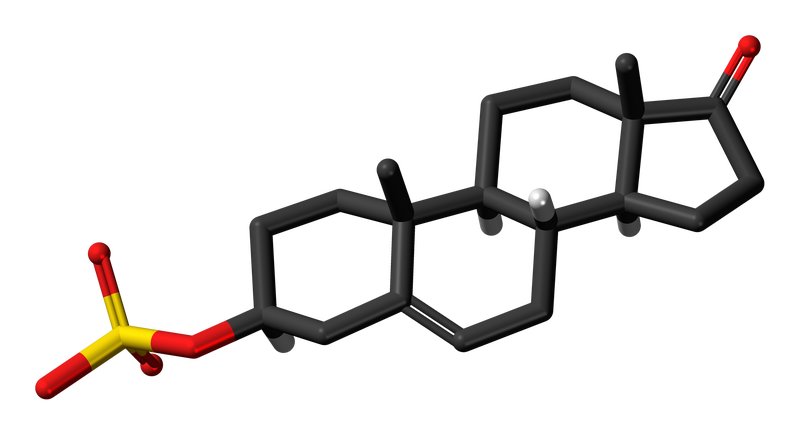

Researchers at the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) on the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio are tasked with studying human performance to answer a not-so-simple question: how do you make the nation’s most physically and mentally elite service members even better? Their solution might come in the form of a new drug. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a steroid hormone and a biomarker of chronic stress, according to Regina Shia, a research psychologist at the AFRL. One small study of young military trainees found that after experiencing a stressful scenario during survival school—like a mock prisoner-of-war camp—the service members who handled stress better had a higher ratio of DHEA to cortisol, another stress-related hormone. The finding suggests that supplementing DHEA, the natural levels of which begin to drop in the human body after our mid-twenties, might help buffer soldiers from the worst effects of stress.

How do you make the nation’s most physically and mentally elite service members even better?

As a nutritional supplement, DHEA isn’t FDA-regulated and thus is available over the counter at places like Walmart and GNC. “The idea behind it is to reduce chronically high cortisol levels,” Shia says. “That’s how it’s supposed to work. Of course, any over-the-counter drug is going to express itself the way that it’s manufactured.” In other words, unregulated supplements contain all sorts of ingredients other than the active compounds, all of which could influence how it works inside the body. When Shia begins her study, she’ll be getting DHEA in its natural form directly from a compound pharmacy or manufacturer. So before you go tweaking your hormone levels with over-the-counter supplements, remember that you’ll be getting more than just DHEA.

Trading Combat Boots for Ballet Slippers

Soldiers in the South Korean Army’s 25th Division guard the border with North Korea along the Demilitarized Zone. To deal with the stress of living full-time on the front lines, the group of about 15 soldiers slip on ballet slippers and dance away the tension. The dance classes are taught by a member of the Korean National Ballet, who visits the base once a week and lines up the service members at the bar to learn the basics of ballet.

“Ballet requires a great amount of physical strength and is very good for strengthening muscle, increasing flexibility, and correcting posture,” Lieutenant Colonel Heo Tae-sun told Reuters in 2016. Dance also reduces stress hormone levels in individuals—as do most forms of exercise. But as a social activity, the benefits of dance extend beyond those associated with simple movement. In South Korea, for example, officials reported that the practice also strengthened the bonds between soldiers, making the unit more cohesive. Research has shown that dancing in synchrony with others can increase pain tolerance, as it appears to activate the endogenous opioid system, which releases feel-good chemicals like endorphins and encourages social bonding. Both the social aspects of dance and the mental effort required to learn and remember choreography can have a neuroprotective effect, boost serotonin levels, and improve mood.

Creative Cure for Stress

Twice a year, in Canberra, Australia, members of the Australian Defense Force (ADF) participate in a monthlong, live-in art therapy program. The ADF launched the Arts for Recovery, Resilience, Teamwork, and Skills (ARRTS) program in 2015 for service members suffering from PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Experts in one of four tracks—music, drama, creative writing, and visual arts—offer training tailored to each participant’s skill level. So far, participants report higher self-esteem, confidence, and resiliency. “I keep a visual diary and lose myself in my art rather than my mind racing and me going downhill,” Corporal Daniel Cooper, a 2015 participant in the visual arts track told the News Corp Australia Network.

Art therapy has long been thought to confer psychological and cognitive benefits by providing budding artists with a sense of purpose and a chance to learn to new skills. Research is beginning to show that taking time to be creative can also have a physiological effect on the body and on stress hormones in particular. A 2016 study from researchers at Drexel University found that after just 45 minutes of making art—for study participants, this meant getting creative with paper, markers, and clay, among other materials—reduced cortisol levels. Beginners and more-experienced artists alike enjoyed a drop in the stress hormones, which suggests that you don’t need a monthlong training course in the arts to reap the benefits of creative activities.